From Cars to Planes and Back Again Four

As discussed in part three of this series, Ford Motor Company’s monumental effort that resulted in its completion and delivery of a record number of B-24 bombers during World War II (WW II), along with their pre-war history as a builder of the legendary Tri-Motor airliner, has resulted in its being the most recognized car company that also produced aircraft.

Ford developed a reputation for aviation excellence in producing Tri-Motor airliners and B-24 bombers

Ford developed a reputation for aviation excellence in producing Tri-Motor airliners and B-24 bombers

Despite building only 200 Tri-Motors and over 8,600 B-24s, only one Ford B-24 exists today (as a non-flying display, seen at right at Barksdale AFB, LA) while at least eight Tri-Motors (including this one at left) remain active

While the Tri-Motor and B-24 are powered aircraft, a lesser-known fact is that Ford has a history of producing non-powered air vehicles as well. Specifically, Ford was the largest manufacturer of military gliders in the U.S. during WW II by building the CG-4A, a 15-place transport glider that was used by the military to swiftly and stealthily deliver troops and equipment in every major military operation of the war. As with the B-24, the CG-4A’s design was not originally developed by Ford but because of its experience with mass production, the company out-produced every one of the other builders of the plane. This is particularly remarkable as the facility that produced the CG-4A was not located in a major industrial area like Detroit or some large population center. Instead, the planes were manufactured at a factory in the town of Kingsford, near Iron Mountain on the remote Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The facility’s extensive experience with producing wood products for Ford cars figured in its selection as a glider manufacturer and this early automotive history is outlined in the next section.

Pre-War Plant History: Any examination of Henry Ford reveals that he was ever vigilant in pursuing ways to more efficiently manufacture products while maintaining maximum self-sufficiency. To this end, he constantly strove to manufacture every part of his vehicles.

By 1919 Ford’s factories in Dearborn and Highland Park were building Model T’s at enormous rates. Henry soon calculated that he could lower his production costs and thus raise profits by owning holdings in all of the raw material sources. Based on information provided by Edward G. Kingsford, who was a Ford dealer and real estate agent in Iron Mountain, MI as well as a cousin by marriage, Ford discovered that he could obtain iron ore, coal, silica, limestone and timber in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Since he had rail and cargo ships available to transport the material Ford quickly developed a plan to purchase as much acreage as needed to create a permanent supply of material for his factories, especially timberland. At that time each Model T sedan required 250 board feet of hardwood; if he could control the supply of that material he could realize a significant cost savings.

With Edward fronting his purchases by the fall of 1919 Henry had acquired 313,000 acres of timberland around Iron Mountain, located on the southwest corner of the Upper Peninsula. Ford immediately began the construction of a huge sawmill in Iron Mountain which began operating on July 12, 1921. By November the 3,000 acre saw mill was shipping its output to Ford’s River Rouge plant to support Model T production. To go along with the sawmill, Ford also built a huge wood-working shop which prepared wood products for shipping to the outside body builder firms that Ford used in Detroit.

Ford’s Iron Mountain, MI plant was located in the timberlands of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula

The remoteness of the location is illustrated by its distances from the cities and major industrial areas of Chicago (300 miles), Minneapolis (313 miles), Detroit (583 miles), Cleveland (665 miles), and Buffalo (832 miles)

Alongside Iron Mountain, the Ford Company started to develop a town which Henry named Kingsford in honor of his cousin-in-law. One hundred houses were built for the mill’s workers, and the sawmill was expanded with a new hydroelectric power station on the Menominee River.

In 1928 two things happened that impacted the plant: 1) Ford launched the new Model A, which used much less wood than the Model T, and 2) Ford got into the station wagon business and decided to manufacture its own station wagon bodies, which were made of wood. The result was that rather than just providing parts the Iron Mountain facility was charged with body cutting and shaping operations. The station wagon body frames were then shipped to Murray Body Company in Detroit or Baker-Raulang in Cleveland who were subcontracted for final assembly.

Ford’s Model 150-A Station Wagon debuted on April 25, 1929

The new Model A used much less wood than the Model T but with the introduction of a station wagon version Iron Mountain’s role shifted to providing maple with birch paneling for the wooden bodies (source: www.airliners.net)

After using a number of outside suppliers and bodybuilders in 1937 Ford ended its wagon assembly contract with these firms and began assembly of all wood-framed station wagons at the Iron Mountain facility. With this change, Ford redesigned the plant to bring full-body production to Iron Mountain during 1937 to 1939. Once complete the station wagon assembly line employed about 300 workers who turned out 70 to 80 finished wagons a day which were then shipped by rail in eight to ten box cars.

Production continued through the 1942 models but with the start of WW II many employees signed up or were drafted for military service. Concurrent with the loss of personnel was the cessation of automobile production for the duration of the war. Both factors brought about the closure of the Iron Mountain mill and woodworking shop. However, this would change as a new tactic in the war required an old technology that was updated and adapted for use by the military: gliders. This vehicle would put Iron Mountain’s remaining and uniquely-skilled workforce back in production of a product that none of them probably ever imagined.

Military Rationale for Gliders: The concept of the combat glider stems from the end of WW I, in which Germany was the loser. Part of the conditions of its surrender prohibited it from having an air force. However, the treaty did not prohibit the building and flying of gliders, so in reaction glider-flying clubs sprang up all over the country. By the late 1920’s German high schools were offering glider flying as a part of their regular curricula. When the Nazis came to power in 1933 the glider pilots became the nucleus of the new German air force, the Luftwaffe.

Given their history with gliders the Germans were the first to use them for military purposes. In their rapid conquests in Europe early in WW II they demonstrated that a cohesive unit of assault troops could be quickly landed to capture or neutralize key targets prior to a main attack by a ground force. This was in contrast to paratroops that were often scattered upon landing and had to spend considerable time forming up in order to become a capable fighting force. Additionally, gliders could carry artillery, vehicles, and supplies with the landed troops, thus providing greater initial firepower, mobility, and lessening the need for immediate re-supply required of paratroops. Taking full advantage of these benefits the Germans were highly successful in their operations, despite taking heavier than anticipated losses in capturing Greece and Crete, causing Hitler to order that gliders or paratroops would never again be used on such a scale.

Nevertheless, Germany’s effective use of glider forces caught the attention of British and American military commanders, who then decided to develop their own combat glider programs. Major General Henry “Hap” Arnold, Commanding General of the Army Air Corps, directed the development of a transport glider program which officially began on February 25, 1941.

A group was soon set up and charged with design and procurement for the glider program. However, with the country gearing up for war and front-line combat aircraft being the number one priority, the group’s prime directive was that no company producing powered aircraft could be approached for glider designs. As a result in March 1941 a preliminary requirement for a 15-place transport glider was sent to eleven companies, of which only four responded. The eventual winner was the Weaver Aircraft Company of Troy, OH, known by the abbreviation of its full name as “WACO” (spelled as “Waco”, pronounced WAH-ko).

|

CG-4A TECHNICAL NOTES: Maximum towed speed: 150 mph Span: 83 ft. 8 in. Length: 48 ft. 4 in. Height: 12 ft. 7 in. Weight: 7,500 lbs. loaded |

The Waco CG-4A was the standard US military glider of WW II

Its fabric covering, aluminum frame, and wooden components made its production amenable to a variety of light aircraft builders and non-aviation manufacturers (source: National Museum of the Air Force)

Waco’s CG-4A design used non-strategic materials, being composed of a tubular metal framework fuselage covered by fabric with the rest of the plane composed of laminated wood glued together under high pressure and heat. It was also well-suited as a transport vehicle, featuring an entire nose section (including the cockpit) that swung upward to create a 70 x 60-inch opening into its cargo compartment. This made it possible to quickly load and unload the glider with cargo including men, jeeps, artillery, supplies, or even small bulldozers. It completed flight testing in 1942, and was in production in that year by many of the eventual sixteen companies that built the aircraft.

Ford’s Transition to Glider Manufacturing: The military anticipated the need for many more gliders than Waco would be able to build in the timeframe that they would be needed. Thus like other programs the government sought other companies to build the CG-4As under license from Waco. With the plant shut down after car production was halted by Federal order in January 1942 the factory needed work, and in March 1942 it was offered a contract to be one of the eventual sixteen builders of CG-4A gliders. After reviewing blueprints and planning for production needs Ford accepted the offer in April 1942 and began the conversion to manufacturing the gliders. This would initially include making an estimated $250,000 in modifications to the plant, training selected personnel on aircraft welding and fabric work, and setting up a supply chain.

Like their counterparts at Ford’s Willow Run bomber plant, the Iron Mountain personnel also found that they had to overcome some serious antagonism when trying to work with the plane’s original designer. This was particularly true when Ford tried to obtain some important half-scale drawings from Waco. After finally receiving the required drawings Ford personnel re-drew them at full-scale and in the process of doing so found many errors. These were brought to the attention of senior engineering management at Waco who apparently had a change of heart about working with Ford, whereupon the relationship improved dramatically from that point.

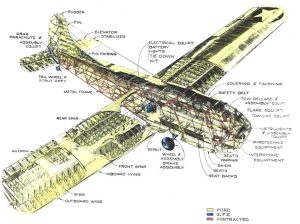

Internal view of a CG-4A illustrates the complexity of the design

Each aircraft required more than 70,000 parts, with the yellow portions provided by Ford, the blue items furnished by the government, and subcontractors providing the items in red (source: Brown/C L Day Collection)

About four months after receiving all of the drawings and design materials Ford hand-built their first CG-4A in Dearborn at the former Tri-Motor factory, possibly doing so as the Iron Mountain plant was still making facility modifications to accommodate glider production. Its roll out on September 16, 1942 culminated in completion of successful testing and acceptance by the Army in November. Glider production at Iron Mountain then began in December, resulting in 12 gliders being produced that month. With the resolution of continuing issues and a 3-shift six days per week schedule the plant worked up producing 130 gliders per month by May 1943. Eventually, even this record was exceeded as 4,500 people working to the same schedule were able to produce eight gliders per day.

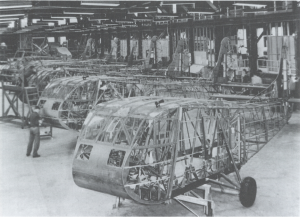

Installation of fabric coverings on CG-4A fuselages at Iron Mountain

Once complete the fabric will be painted and the wooden floor installed. Note the lack of an automotive-style assembly line due to limitations of the building’s internal structure (source: Cornish Pump & Mining Museum)

Glider Production at Iron Mountain: Although it appears to be a relatively simple design, the CG-4A was made of more than 70,000 individual parts. Additionally, some 4,000 special fixtures were needed to process glider parts. Ford’s Plant Manager Walter Nelson recalled that they made many changes in the glider and it “was the only one that came into Europe in which any or all parts were fully interchangeable”. Achieving this level of production was a major accomplishment because the facility’s internal layout precluded Ford from using an automobile assembly line for the planes, so that each glider had to be completed at one location. In fact, major glider components were constructed in several different buildings on the plant site.

After each CG-4A was fully assembled military inspectors at the plant would perform a quality check. If the gliders passed inspection they would then be disassembled by Ford employees and crated in large wooden boxes for rail or truck shipment to their required destinations. Five crates were required to ship one glider, ranging in size from eight to twenty-five feet in length. Starting in 1944 shipping was speeded up considerably when Ford cut a 120-foot-wide swath through wooded areas leading from its assembly line to the airport one mile away in Kingsford. Fully assembled gliders could then be pulled by Ford farm tractors and hauled to the airport. Because the field was too small for towing aircraft to takeoff with gliders attached, Ford implemented aerial retrieval or “snagging” of the glider towropes from the air, a standard tactic for retrieving empty gliders from combat zones. After picking up the gliders at the field the towing airplanes would pull them to their destinations around the country, saving valuable delivery time as well as costs to pack and ship the gliders.

Completed gliders could be shipped in pieces by rail, truck, or towed as a complete vehicle by aerial pickup

The trucks used two Ford flathead V-8s mounted side-by-side and were slow while aerial retrieval was faster and didn’t require costly disassembly/packing (source: top LIFE Magazine, bottom Popular Science, February 1944)

In June 1943, Ford received a contract to build Waco’s larger CG-13A glider, the first of which flew from the Dearborn Airport on 6 January 1944. The CG-13A could carry forty fully equipped troops, was stronger than the CG-4A, had more instruments, and had flaps for better control of its descent to a landing. Although no CG-13A gliders were flown in combat in Europe, one was flown in combat in 1945 in the Philippines. Ford’s original contract was for 150 CG-13As, but after the D-Day landings the contract was canceled after 87 were completed.

The CG-13A was also a Waco designed glider that was designed for higher capacity payloads

It had the same length as the CG-4A but had a greater wingspan and was able to carry 30 troops, twice the number of its predecessor (source: The Henry Ford Collection)

By the time that glider assembly ceased the Ford facility had pioneered several cost-saving production processes. For example, they found that by pressing special rubber tubes carrying hot steam against the plywood skins where they were glued to the ribs the normal curing time of six to eight hours dropped to about ten minutes and resulted in excellent bonding strength. Ford’s efforts were rewarded on June 21, 1944 when the Iron Mountain plant received the Army-Navy “E” Award for excellence in production. An Air Force officer at the presentation stated that “less than 3 percent of the 90,000 plants throughout the country are now flying an “E” Award”. Over twenty thousand people watched the awards ceremony, followed by demonstrations of glider tows and landings. The plant later won a second “E” Award in February 1945.

The Kingsford plant eventually turned out 4,190 of the total of 13, 903 CG-4As built, more than twice the number of gliders produced by any other company during the war. Additionally, because of its success in developing more efficient manufacturing processes Ford charged only $15,400 per glider versus a minimum of $25,000 charged by the fifteen other manufacturers.

Postwar Plant History: At the end of the war station wagon building resumed at Iron Mountain, with the factory initially producing dressed up pre-war models. All of the Ford and Mercury station wagons and Sportsmen convertibles were built here.

After the 1948 models were completed Ford introduced the “New Generation” cars, in which steel replaced about 85 percent of the wood in the station wagons. No structural wood was required as the wagon bodies were steel structured with mahogany-skinned panel work and maple framing. The steel body structures were built in Detroit and then shipped by rail to Iron Mountain. Here the wood panels were installed and the bodies were painted. The work required a lot of hand assembly to make the doors and side panels fit cleanly.

View of trim assembly line at the Iron Mountain plant circa 1949

Note how there is much less wood on what are to become Ford’s popular Country Squire station wagons in comparison to the earlier 1920s – 1930s models (source: Menominee Range Historical Museum)

Ford continued building the Ford and Mercury station wagons at the Iron Mountain plant until December 1951, when the entire facility was closed and 3,500 workers were laid off. To take up the loss of production of Ford and Mercury station wagons, production was moved to Ford’s subcontractor Mitchell-Bentley in Ionia, MI.

A completed 1950 station wagon at Iron Mountain circa 1949

Photographed against the backdrop of the plant’s saw mill and power plant, this model was produced in the last years of automobile production at Iron Mountain (source: Menominee Range Historical Museum)

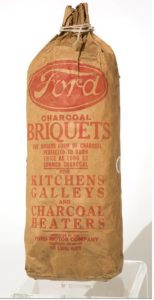

Charcoal Takes Over: As an adjunct to the original saw mill Ford built an onsite chemical plant in 1924 that was designed to process the vast amounts of scraps left over from making wooden parts and casings for its Model T cars. At its opening this facility employed 140 men who were charged with distilling the wood scraps to extract methanol and ethyl acetate. The methanol was used for formaldehyde and anti-freeze production and the ethyl acetate was used as a solvent by the paint industry. The waste from the distillation process was powdered charcoal that amounted to about 610 pounds per every ton of wood. Ford found a unique way to dispose of this material. It was mixed with a binder, compressed into the now familiar pillow-shaped briquets (note: Ford’s spelling), and sold for use in domestic cooking and heating. For many years the briquets were only available for purchase through Ford dealers.

After Ford closed the Iron Mountain site a group of local investors acquired the chemical plant and operated it as the Kingsford Chemical Company, making “Kingsford Charcoal Briquets” until 1961 when it relocated to Louisville, KY. The Clorox Company acquired the Kingsford Charcoal brand in 1972 and retains ownership and charcoal production today at a number of locations. The sawmill, powerhouse, and distillation building were torn down after Kingsford Chemical pulled out, but the three body buildings, a maintenance building, and the drying kilns from the original plant are still there and are occupied today by other businesses.

Charcoal packaging at the Ford Chemical Plant at Iron Mountain in 1924

After processing leftover scraps from making wooden components for use in Ford’s Model T, the company produced charcoal briquets and made this a very profitable business (source: Menominee Range Historical Museum)

For more information about the history of Ford’s Iron Mountain plant, its role in manufacturing gliders as well as their general use in WW II, here are some sources:

- Armagnac, Alden P, “Silent Partner of the Plane”, Popular Science, February 1944

- Bryan, Ford Richardson, Beyond the Model T: The Other Ventures of Henry Ford, Wayne State University Press, 1997

- Cummings, William John, Photographs of Kingsford, Dickinson County, Michigan – Ford Plant, http://www.dcl-lib.org/images, retrieved April 14, 2014

- Day, Charles L, Silent Ones: WW II Invasion Glider Test and Experiment, Charles L. Day, 2001

- The Henry Ford Online Collections, http://collections.thehenryford.org/Collection, retrieved April 14, 2014

- Stoff, Joshua, Picture History of World War II Aircraft Production, Dover, 1993

CONTINUE TO PART 5