A New Height In Publicity, Part 1

Automobiles and airplanes began to develop in parallel starting in the early 20th century, spawning numerous instances in which their respective technologies or products came into direct contact with each other. In some cases, these encounters contributed to the advancement of some aspect of their respective industries, while others were interesting whimsical occurrences. The story that follows is of an event that falls within the latter category. It unfolds in two parts to present a meeting of automotive and aviation technology that was brought together for an interesting purpose and in a most imaginative way.

The 1930s saw many advances in aviation technology, but this scene does not depict the latest flying car design. Instead, the photo illustrates a key feature in the story of an innovative stunt that was part of a national advertising campaign by Sunoco.

In 1935 the country was firmly in the grip of the harsh economic climate of the Great Depression, and like other businesses gasoline companies were fighting a major battle with each other for customers. Against this backdrop, the Sun Oil Company, familiarly known as Sunoco, was seeking a market differentiator. As a result, the company began to explore new ways to position their Blue Sunoco gasoline. This product was a premium one-grade gasoline that had been developed in the late 1920s and was known as “the high-powered knockless fuel at no extra price”. Unlike other gasolines, it did not contain tetraethyl lead to boost octane rating and prevent knocking. Blue Sunoco was a major contributor to the company’s growth with the result that by 1940 it would have 9,000 stations, and would help to establish Sunoco as a high-quality fuel supplier for many years.

However, in the grim reality of 1935, this success was not yet apparent for Sunoco’s beleaguered retailers. Thus, the company’s marketing team came up with the idea to publicize another feature of Blue Sunoco, which was that Blue Sunoco provided excellent performance in the harshest temperature extremes. This performance was quantified in cold climates by the fact that an engine supplied with Blue Sunoco would start at 0°F in ⅕ of a second. To demonstrate this capability in a spectacular way, Sunoco’s marketers made a decision that was in no small part a reflection of the times: they would use airplanes to carry out a test to confirm the company’s claim.

To answer the question of how to carry out what was in essence a stunt, the answer they came up with was to carry by airplane an externally-mounted stock automobile filled with Blue Sunoco gasoline to an altitude where 0°F temperature was present. Unbiased observers in an accompanying plane would watch a driver enter the suspended car and instantly start its cold-soaked engine, thereby proving the superior quality of Blue Sunoco.

The second question as to why they decided to use airplanes for the demonstration comes back to the noted sign of the times. After Charles Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight, a number of aviators were continuing to undertake their own attempts to complete record-setting flights. Aviation was akin in cachet to information technology today, with pilots portrayed by the media as technically superior individuals and bold explorers who were undeterred by the risks in their undertakings. These portrayals also had a tendency to cast these individuals as highly trustworthy, thus making them natural candidates to enlist for overt or tacit commercial endorsements.

In their checklist of major requirements to carry out this stunt, Sunoco’s marketing team listed the following four items: test car, test car driver, airplane, and pilot. The first item was easy, as Sunoco had a new 1935 Ford roadster immediately available to use as the test vehicle.

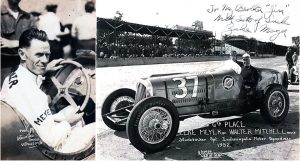

For the driver, Sunoco followed the standard marketing playbook by seeking a recognized celebrity in securing the services of race car driver Herbert “Zeke” Meyer. Like many of his contemporaries, Meyer survived a number of hair-raising experiences, including a trial in which he drove blindfolded through Hartford, CT. In addition, he competed in the Indianapolis 500 four times in his 13-year racing career. Driving a Studebaker, in 1932 he achieved the first of two unbroken records at Indianapolis by finishing with the highest number of positions gained during a 500-mile race at the track; starting at 38th place, he finished in 6th place for a gain of 32 places. His second record occurred in the 1936 race, where accompanied by his son Chet as his riding-mechanic (standard procedure for the period) he led the only father-and-son team to compete as driving participants. The team finished 9th, also in a Studebaker.

In his career Herbert “Zeke” Meyer never won a race, but he was very well-known for his record finish in the 1932 Indianapolis 500, where he started in 38th place and ended up in 6th place.

Finding a plane capable of carrying an externally-mounted car turned out to be a bit harder. The major manufacturers such as Boeing, Douglas, and Lockheed did not have an airplane that could handle the task. Their designs followed the standard convention of payload distributed longitudinally in a cigar-shaped fuselage, making them not structurally robust enough to carry the concentrated load of a 2,700 lb. automobile.

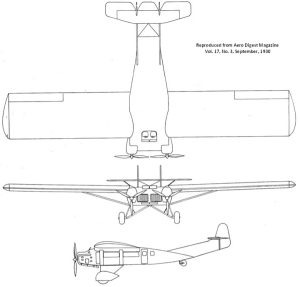

However, there was one machine that appeared to be more than capable of fulfilling this requirement. The Uppercu-Burnelli UB-20 was one of the first all-metal, stressed-skin, high-winged monoplanes. This aircraft was developed in a teaming arrangement between investor Inglis M. Uppercu and designer Vincent Burnelli at Uppercu’s Aeromarine Plane and Motor Co. factory in Keyport, NJ. Powered by two Packard 750-hp liquid-cooled engines, the UB-20 was an unconventional design whose fuselage was shaped like an airfoil. The result was that instead of simply dragging through the air and unnecessarily burdening the wings, the fuselage of the UB-20 generated its own lift as a contribution to the aircraft’s performance, notably an ability to carry a three-ton load. In addition, the lifting-fuselage provided the bonus of a 12-foot-wide cabin and resulting widely spaced landing gear that could easily accommodate an external load of the size of the Ford roadster.

The Uppercu-Burnelli UB-20 was the only aircraft that could support the stunt due to its extended wheel track and its 12-foot-wide lifting-fuselage configuration. Clearance between payload and ground due to its tailwheel setup was easily resolved. Below left, Inglis Uppercu was an Autocar, Cadillac, and Packard car dealer in the New York-New Jersey area. In 1908 he got involved in aviation, then founded Aeromarine Plane and Motor Co. in Keyport, NJ in 1914. Vincent Burnelli is shown with wind tunnel models of lifting-fuselage designs of which he was an ardent life-long proponent. At right is an aerial view of the Aeromarine plant that formerly built military flying boats and seaplanes, now advertising the Uppercu-Burnelli partnership.

To fulfill the requirement for a pilot, Sunoco’s marketing department apparently followed the same script utilized in selecting Zeke Meyer. Thus, Burnelli personally spoke with Louis T. Reichers regarding his interest in piloting the UB-20 due to his expertise and notoriety that ensued from two highly publicized experiences.

The first was an attempt to make a solo flight from New York to Paris starting on May 13, 1932, in which his goal was to complete it in half the time as Lindbergh’s 33 hours. He was well on the way to a planned refueling stop near Dublin, Ireland, but an erroneous weather forecast caused him to run out of fuel just 15 miles short of the Irish west coast. After spotting the passenger ship President Roosevelt and being knocked out after landing at sea nearby, he was saved from possibly drowning through a dramatic rescue by ship’s personnel.

His second experience, and possibly most important one, occurred on January 13, 1935, when he was the pilot of another Burnelli aircraft designated UB-14 that crashed due to mechanical issues on a test flight at Newark Airport, NJ. Newsreel cameras captured the event, which occurred just a month before the Sunoco test. Reichers was slightly hurt in the crash. Accompanying mechanic John Murray incurred serious injuries because he was in the cabin and not strapped in, but later made a full recovery. Burnelli had touted the crashworthiness and resulting increased survivability of his lifting-fuselage design on the UB-14 and the similar UB-20. This feature was credited by Reichers in a post-crash written report as saving the lives of him and his crewman. It, therefore, seems reasonable that Reichers and Burnelli had a high level of mutual regard stemming at least from the UB-14 crash; if so, it may have helped to make Reichers more receptive to discussions with Burnelli about the stunt.

Reichers’ report on the merits of the “lifting body type of design” after the 1935 crash of the Burnelli UB-14 was submitted by Vincent Burnelli to Congress’ Safety in Air Navigation hearings on April 2, 1947. The report was part of Burnelli’s testimony after being requested to appear and answer questions about the increased safety of his designs vs. then-current technology.

However, as Reichers related in his book The Flying Years (Henry Holt & Co., NY, 1956), when Burnelli first presented the idea of the stunt to him he thought it was crazy as well as needlessly risky. Burnelli began to sway him with the publicity aspects of the stunt, as he knew this was something that Reichers would particularly appreciate. This is because Reichers was employed as the personal pilot of Bernarr Macfadden, a wealthy publishing magnate who was also a shameless publicity seeker. Reichers had played this trait to his advantage in cajoling Macfadden to let him use his personal aircraft in various air races and record flight attempts (including his ill-fated transatlantic flight). Nevertheless, given the unusual nature of the stunt, Reichers checked the measurements of the roadster and airplane to confirm its viability. He discovered that adequate ground clearance for attaching the car to the plane was the major issue, but with some work this obstacle could be overcome. The remaining question for Reichers was compensation for his efforts. Burnelli was well-prepared with details. Reichers could expect to make at least $1,000 by Sunoco paying all of his expenses, plus $100 per week for four weeks, and a bonus of $400 for each flight with the car. Upon completion of the flight, Reichers would have to make several radio appearances with Sunoco’s radio newscaster Lowell Thomas (Thomas later made the first TV news broadcast on July 7, 1941, and announced the news on both radio and TV into the 1960s) at a fee of $100 for each interview. As Reichers states in the aforementioned book, Burnelli’s $1,000 estimate was a compelling argument; today that sum would be equal to $22,000. In an industry where even before the ravages of the Great Depression, participants were often quoted as stating that the greatest danger facing anyone in aviation was starving to death. Given that perspective, this offer was too good to pass up.

Now that all of the required items were in place, Sunoco’s team began the work of mating the car to the plane. First, they removed the roadster’s convertible top. Then they had to address the issue of clearance between the car and the ground, as the UB-20 sat at a nose-high angle due to its tail wheel configuration. To overcome this challenge, mechanics added ten more pounds of air into each of the UB-20’s tires, thereby increasing ground clearance by 2 inches. Another 4 inches of clearance was gained by jacking up the Ford’s rear axle and strapping it there. Finally, the crew deflated most of the air in the Ford’s tires, with the result that clearance between its rear wheels and the ground was now a tight but workable 6 inches.

Reichers poses with the UB-20 and attached Ford roadster. Note that Zeke Meyer is seated in the car, with his head poking just above the driver side door. Both views illustrate the low clearance between the car’s rear wheels and the ground.

Per Sunoco’s plan, for safety reasons the flight was to be made over the New York City metropolitan area, thus not directly over the city. The UB-20 would takeoff from and land at the city’s Floyd Bennett Field, since it had concrete runways that were well above what the aircraft needed for safe operations. It was wintertime, and the ground-level temperature was running from 10°F to the low twenties. With a normal temperature reduction of 3° for every 1,000 feet of altitude, Reichers could expect to find the required 0°F between 3,500 and 7,000 feet. Once the UB-20 reached the right environment, Zeke would open a trap door in the plane that allowed him to drop down into the car to start the engine. When he pressed the starter a light on the windshield lit up and went out when the engine was running, allowing personnel in the observation plane to time the sequence and confirm that engine start occurred as advertised. Further, the car’s white rear wheel rims were painted with a black spiral stripe; when the engine started they would spin and be filmed from the observation airplane. The observation plane’s pilot, famous aerial photographer, and surveyor Victor Dallin, would signal Reichers when the camera crew had completed their work. Both aircraft would then break off and land back at Floyd Bennett Field.

It now seemed like everything was ready, but now Sunoco added one more hurdle to the project. As a prudent measure, Sunoco’s management insisted upon full insurance on the stunt. Their insurer dutifully sent a representative to the airfield to check out the fully configured UB-20. He was satisfied with the installation, but then he dropped a bombshell: he requested Reichers to take the UB-20 and roadster up to 500 feet and do a series of figure eights! This mandatory requirement would allow the representative to observe the aircraft in flight in order to confirm that there were no control problems. There would be no insurance without it.

Reichers paused for a moment in thinking initially that this was a joke. When he realized that the man was serious, he was incredulous. Perhaps not wishing to reveal his concerns over the car’s untested impact on the plane’s handling, his vehement response was that this was outside of the scope of his agreement for the flight. He planned to simply take the plane and car up and down in as little time as possible. The insurance representative held his ground in that there would be no stunt without the flight test. After much on-site discussion and phone calls to the insurer’s management, both parties agreed to a compromise. Reichers would taxi the UB-20 to the end of the runway and takeoff, fly to an altitude of three feet, then land straight ahead on the same runway. This face-saving action allowed the insurer to cover the flight so that it could finally proceed. Sunoco then announced that the flight would take place at 10:00 am on Tuesday, February 12, 1935.