The Indianapolis Not-Quite-Nine

When the checkered flag waves over the winner of the 100th Indianapolis 500 this Sunday, it will, as is customary, signify the end of the race. But it was not always so.

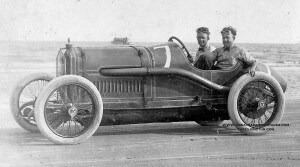

In the early years of the 500, when the winner crossed the finish line, the race would continue until all cars capable of completing the 500-mile distance had done so. Given the lower speeds of the era as compared to today, this process took some time. Which is how it came to be that Ralph Mulford, known in the racing circles as Smilin’ Ralph, set a record in the race of 1912 that still stands today.

In 1912, prize money was available only to the top ten finishers, and the rules further required competitors to complete the full 500 miles in order to earn the cash. Mulford, whose car was suffering mechanical problems that made numerous pit stops necessary but well-aware of the high rate of attrition, was determined to be one of those ten. So he persevered, continuing to drive long after winner Joe Dawson had taken the checkered flag, and long after virtually everyone had gone home.

So lengthy was Mulford’s journey to the finish that one of his pit stops was for a quick dinner, widely reported to have been fried chicken and ice cream. A dinner break would seem a necessary stop, because Mulford finished 8 hours and 53 minutes after the start of the race. He finished his 500 miles in front of grandstands that had once been packed but were now empty, and under a sky that was once bright with the noonday sun but was now tinged with the last rays of sunset.

Mulford’s race speed was an average of 56.285 mph, a record which will remain unbroken: The slowest finishing speed in Indy 500 history.

Mulford’s race speed was an average of 56.285 mph, a record which will remain unbroken: The slowest finishing speed in Indy 500 history.

Today, soccer parents in SUVs exceed that average in between cub scout meetings and play dates.

Sunday’s 500 will be concluded when the winner completes 200 laps, with all others being credited for however many laps they completed to that point and their position relative to their competitors. Every driver, including the last-place finisher, will earn a share of the more than 13.5 million dollars in prize money. But even if it were still required to go the full distance in order to get paid, it would likely not take very long. This year’s slowest qualifier, Buddy Lazier, qualified at 222.154 mph.

Images selected from The Old Motor.